What started as a company in Silicon Valley, has established itself as a successful space-startup in Europe. The Italian company D-Orbit offers services to both traditional and new space in the domains of satellite manufacturing, launch, deployment, operations, and end-of-life solutions. By offering the delivery of satellites to any orbit, D-Orbit intends to establish itself as a leading transportation service for the developing ride-share market in the space sector.

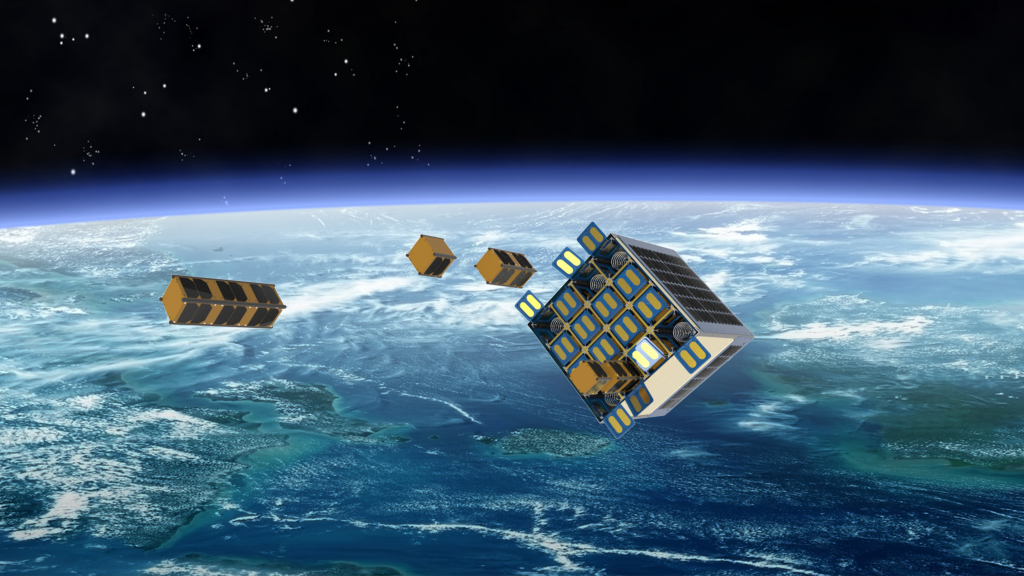

Earlier this month, D-Orbit won a contract to launch ten Astrocast cubesats as secondary payloads on a future Vega mission in 2019 or 2020. The company currently uses standard CubeSat deployers but is currently developing the unique ION launch service that will serve as a free-flying dispenser to deploy up to 48U of CubeSats.

We spoke with CEO of D-Orbit, Luca Rossettini, to learn more about the mentalities he took from Silicon Valley, the unique service offered by his company, and how his team was able to succeed as a start-up in the European space industry.

Image above: Luca Rossettini, Chief Executive Officer of D-Orbit

Spaceoneers: Tell me a little bit about D-Orbit and how your business came about

Luca Rossettini: We work in space logistics, in space transportation. We believe that transportation will be increasingly important for space in the future. There is no business on Earth that can work without transportation and the same applies to space. When travelling to space, we are bringing our own vehicle with us every time. This is very expensive and very complex. There are also companies that are thinking about asteroid mining – they will need a transportation service. There are companies that are building facilities that in the future can host hotels and people – they will need transportation. We believe transportation will be an important part of the future.

For the moment we are transporting small satellites. We have a larger satellite that can include up to 16 3U satellites (or 8 6U or 4 12U, etc) – it is modular and configurable. Once our vehicle is released in orbit by the launcher, we have our own propulsion, so we can change the orbital parameters while we deploy the constellation of satellites, saving 85% of time that is usually required by satellites to get where they need to go. We are much like a small DHL truck with lots of packages; we deliver them where they need to go. We also move satellites at the end of life. We have systems you can install on the satellite before it is launched that are able to then remove the satellites at the end of their life. This is what we are doing right now.

Spaceoneers: How is the configuration bus different to NanoRacks?

Luca Rossettini: The difference between NanoRacks and others is that we don’t just put the satellites into a standard deployer attached to the launcher. We aggregate a batch of satellites into a real transporter, a bigger satellite that can be detached from the launcher. We can release the satellites when we want: one at a time, at different speeds, in different locations, and on different orbits, all within one single launch. With NanoRacks, you have access to the ISS orbit and I believe they can find an added value by working with us. While others can launch satellites only where the main payload is going, we take you wherever you want – this is the main difference.

Spaceoneers: You entered the Space Exploration Masters competition and you won the prize of the ICE Cubes service. Tell us more about this.

It’s a small propulsion system based on 4 independent thrusters that you can install on small satellites, namely CubeSats. The original idea was generated by a different objective. The idea came to me when I visited Planet Labs, back in 2012; they basically had just started their business in San Francisco and already had some CubeSats already built. I went to visit some old colleagues from NASA and I asked if they are planning to remove their satellites at the end of life. They said the satellites are so small, they do not last long enough in space and they will then burn in the atmosphere. I said, why not extend the life of your satellite? They argued that there is not enough space on the satellite to support this feature. I decided to look into it. We found out that if the system is configurable and supports 4 thrusters, it is possible. With 2 of these thrusters, you can increase the orbit after it begins to decay, then you still have 2 thrusters left. You can use one at the beginning of life for dispersion (to separate satellites from each other very quickly) and the last was meant to be a decommission thruster. It does not matter if your satellite is small and will burn up in the atmosphere (and we know that there is also concern about space debris and such small satellites cannot support significant propulsion systems) but with this one you can accelerate the decommissioning phase. This was the original idea.

Then we saw that there are many other applications. For example, imagine a mission going to Mars with small satellites. Your satellite will be released in an Earth-Mars transfer orbit then you need a thrust to insert it in orbit around Mars. These thrusters could be used to do it. Or, if you want to use small satellites for space exploration and you wish to land somewhere (like on a planet or an asteroid), you’ll also need a braking system. You could use a parachute for Mars for example, but this would be very big and heavy. These thrusters allow you to descend on Mars as well. So, of course it doesn’t provide a complete solution for conducting all manoeuvres in space, as it is an expendable propulsion system, but it allows you to pursue other activities that would be very difficult to do with other technologies.

Spaceoneers: You had your first satellite launched last year. How does that differ to FENIX with a small propulsion system for example?

Luca Rossettini: We launched D-Sat, a CubeSat that we built in house along with its own decommissioning system that was meant to do several things. Apart from some activities that we were doing for our customers (we had 3 payloads on board), our decommissioning system is based on the same technology as FENIX: it uses solid propellant. The motor tested on D-Sat however is much larger. Our idea was to simulate the behaviour of a decommissioning system as if it was installed on a much larger satellite. We could not afford to launch a larger satellite, but the overall system was designed to be much larger. We went through test manoeuvres to simulate the end-of-life of the satellite. The decommissioning system activated and it correctly detected its location. When it received a command to fire the motor, the motor fired perfectly. We generated the expected delta-V. While we didn’t accomplish the re-entry manoeuvre because of a misalignment issue (due to a miscalibration of an instrument, our target for the testing the decommissioning system went very well. FENIX, it is the same technology but miniaturised. The intelligent part of FENIX is much smaller and is based on a different mechanism. We need to make sure that this miniaturisation will still be able to work in microgravity (as it is based on memory-shape alloy) and that the new system has the same degree of safety that we had on the system thaw tested with D-Sat. This is what will test from the ISS on the ICE Cube service.

Spaceoneers: What were the biggest challenges in getting going with D-Orbit as a company?

Luca Rossettini: The challenges that we are facing are all related to the growth of the company. In 2018 we are essentially doubling the amount of people of the company. It’s not easy to find people on the market and finding the good ones is hard there is a lot of competition. We need to find good engineers, good salespeople and many other roles and functions for the company. With a limited amount of time you have to be quick. This is a challenge. Secondly money. When you’re growing, you are increasing your sales. So, you have higher costs. If you want to grow faster, you need more fuel. We are using a set of different financial instruments in order for us to keep going at this pace.

Spaceoneers: How did you get your first team together?

Luca Rossettini: I was working at NASA Ames, in California, where I met my co-founder. He was working on other activities but we started working together on the original D-Orbit plan and eventually we decided to come back to Europe to fund a company. All of the other team members we selected were based largely on resilience and capability (particularly of managing people). The first people you hire are those that will lead other people in the company in the future. We are now based in Milano and we have a subsidiary in Lisbon, Portugal (where we produce software for critical applications) and we have a subsidiary USA in Washington, DC. We mainly moved from Silicon Valley due to the trouble with the time zone differences with the subsidiary. The coordination was not easy when we were very young and with very few people.

When we were there (Silicon Valley), in 2009 and 2010, there was less interest in “New Space” and commercial space. So when we decided to fund the company, we thought if we will do it here in the USA, it would be hard as foreigners and we would be dealing with investors that may want to remain local as much as possible. The second disadvantage is that there are many companies in Silicon Valley with very clear and well-understood businesses. We were proposing something crazy related to space activities that investors did not really understand. There is lots of money here, but there were two big disadvantages. In Europe, the start-up system had basically just started. We thought that coming back to Europe with the Silicon Valley mentality could be an advantage. Of course, less money, but also more visibility. This is actually how it happened and this allowed us to get the first and second investors on board. There was less money than what we might have gotten in Silicon Valley, but still enough to start the company.

Spaceoneers: Surely there’s more venture capital in Silicon Valley, but you think the exposure in Europe was beneficial?

Luca Rossettini: That’s something that Europe is missing: the capital for growth. If you have a start-up now, you have plenty of venture capital funds that can give you funding ranging from a few hundred Euros to one million Euros to start your business. However, if you are in the revenue phase but are not profitable yet, then you need to scale up so you’ll need tens of millions. In Europe, it is very hard to find this size of money. Most of the companies that I know are moving away to China and US as well. We are resilient. We are able to make revenues, and this allowed us to stay here.

In the US you have a lot of companies. There is lots of money, but also lots of companies looking competing for it. If you have a very good business that is structured very well and you know how to deal with investors, I believe you have a chance here in Europe as well.

Spaceoneers: What do you believe you brought or took from Silicon Valley?

Luca Rossettini: I brought the mentality regarding how to structure work in the company. For example, in Germany much of the companies have their employees scratch a card when you enter at 9 am, and again at 5pm when you leave. We had to change this according to the labour law in Italy and it was not easy, but for us there is no time required so we set objectives and the people can work whenever they want. We had to adapt to the labour law in Italy and it was not easy. In winter, much of the people go for skiing on Wednesday because the cost is less, then they work on Sunday. This was very helpful. Another aspect is structure. In the US, you have methodologies for everything. You of course need talents, but with methodologies, talent can also teach the new employees how to do everything.

We left in Silicon Valley another type of mentality that I don’t like: the firing of 20% of employees every year. The principle is to keep the best in the company. If you fire 20% every year, the 80% remaining should be better and better. However, I believe in doing that, you create a bad competition between the people of the company. What you really need when you start a business is cohesion between the whole team. In D-Orbit, since we couldn’t find a lot of money, we had to help each other in different functions and I believe this worked very well.

Spaceoneers: Is there any advice you would give to others starting their own space start-up?

Luca Rossettini: Evaluate the money that you will require to go through the process and the market in which you decide to get in. In space now, everyone is jumping in to IoT, data, Earth observation, constellations, and so on, but if you are living in Europe you will have to face that fact that you may not find the same amount of money that the corresponding American companies that are doing the same thing are able to find. Rather focus on something that others are not doing: be the first mover and find your niche. In Europe especially, if you find your niche, you have good possibility.