Astroscale is the first private company with a mission to secure long-term spaceflight safety by developing space debris removal services. The company is actively working on its first technology demonstration mission, intended for launch in early 2020. Astroscale plan is to develop reliable on-orbit technologies to mitigate any potential future debris and safely remove the most threatening space debris in Earth’s orbit.

We spoke with the COO of Astroscale, Christopher Blackerby.

Spaceoneers: Can you explain how Astroscale got started?

Christopher Blackerby: Astroscale is 5 years old. It was started by a Japanese entrepreneur, Nobu Okada, who was in the IT business. He always loved space and was looking at the industry’s big issues by attending space conferences like IAC. He observed that the presentations that highlighted the issue of space debris were typically academic and focused on intuitional missions, with no clear developments of a sustainable solution to stabilise or reduce the debris problem, with the greater goal of reducing the likelihood of potential collisions. He decided to start a for-profit company to find a way to remove debris. It began with just him and we now have over 50 people and have raised $52* million dollars in funding. We have our first tech demonstration mission planned for launch in early 2020.

Spaceoneers: How did you get involved with the company?

Christopher Blackerby: I worked for NASA for nearly 14 years, primarily in Washington, D.C. in the policy and strategic planning area. In 2012, I was sent to Tokyo as the representative for NASA in Asia. I spent 5 years at the US Embassy in Tokyo covering all aspects of NASA’s cooperation in the region. By the time my term had finished, I had met many people in the space industry in Japan. One of these people was Nobu Okada (the founder and CEO of Astroscale). As we were talking, there was an opportunity for me to join the management team at Astroscale. He had the vision at the time with about 25 people to start going global. He had just opened an office in the UK that was doing business development and focusing on the creation of a ground station. At the time, he was looking to expand the international presence of the team. That’s when I came on.

Spaceoneers: Astroscale is looking to reduce the amount of space debris and to raise public awareness about space environment issues. Can you explain why space debris is such a big problem and how you aim to address it?

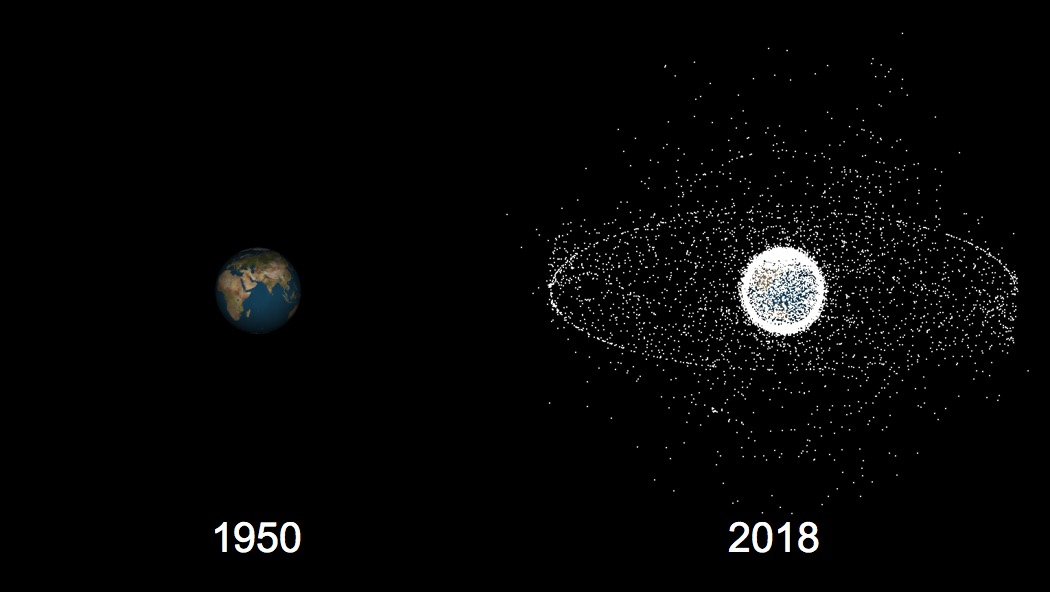

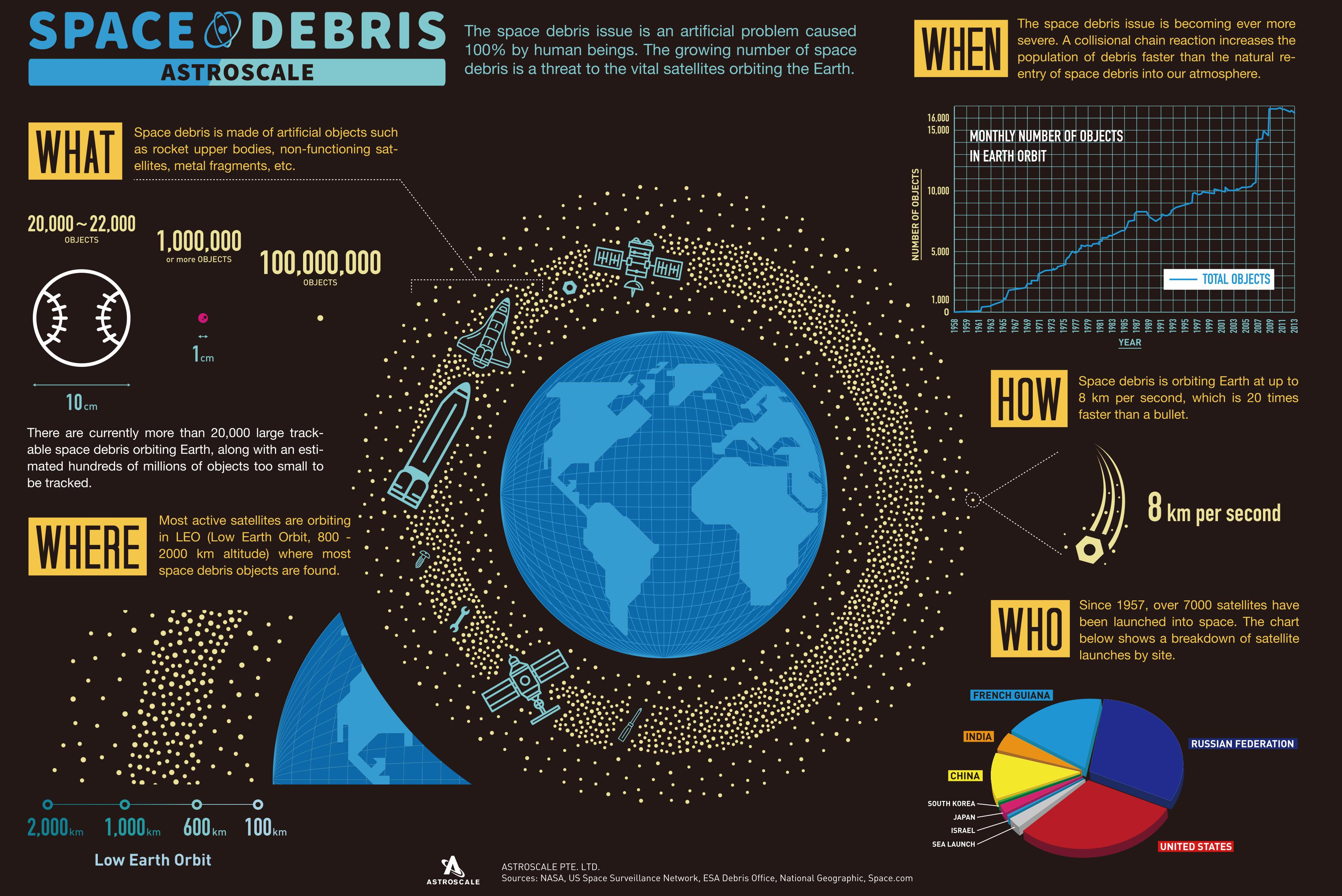

Christopher Blackerby: First of all, we rely on space every single day. Space may seem distant and not tangible, but we use it on a daily basis when talking to friends, checking finances or the weather. It’s a vital aspect of our daily lives. There are a lot of satellites up there, but many of them are old or have stopped working. There are many rocket upper stages that launched but have not come down yet, there are pieces of paint and small parts that have fallen from satellites. There are millions of tiny pieces. But when we get up to debris pieces that are the size of a softball (something of this size could easily destroy a satellite), there are over 20,000 pieces of debris in orbit. These are posing a constant threat to the services that are provided by all these satellites that we continually rely on – this threat needs to be reduced. If any of those accidents do happen, they will create thousands more pieces of tiny debris, making for thousands more potential collisions. The Kessler syndrome or effect postulates that as all these accidents happen, the number of future possible accidents increases exponentially until space becomes unusable. We want to reduce that likelihood.

We are not trying to bring down every piece of debris, but to reduce the risk that is being posed. To do this, we are pursuing two different business paths. The goal of the first is to not create any new debris. When launching any future satellite, we want to make sure that it can safely come down. Even if it fails, it needs to be equipped to be brought back down to Earth without posing any threats.

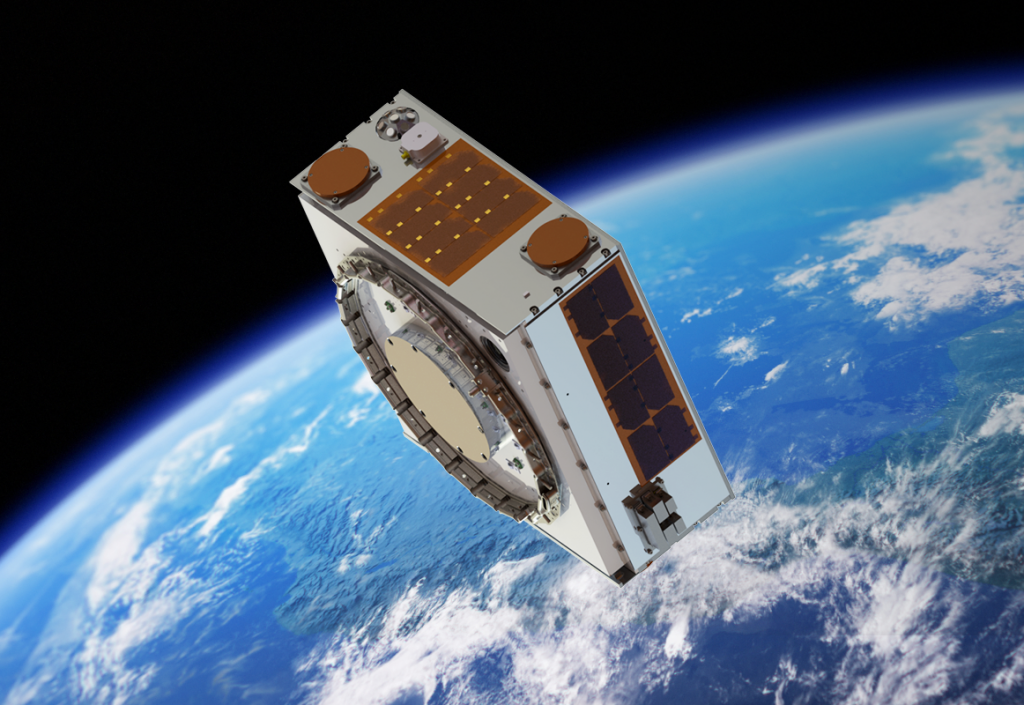

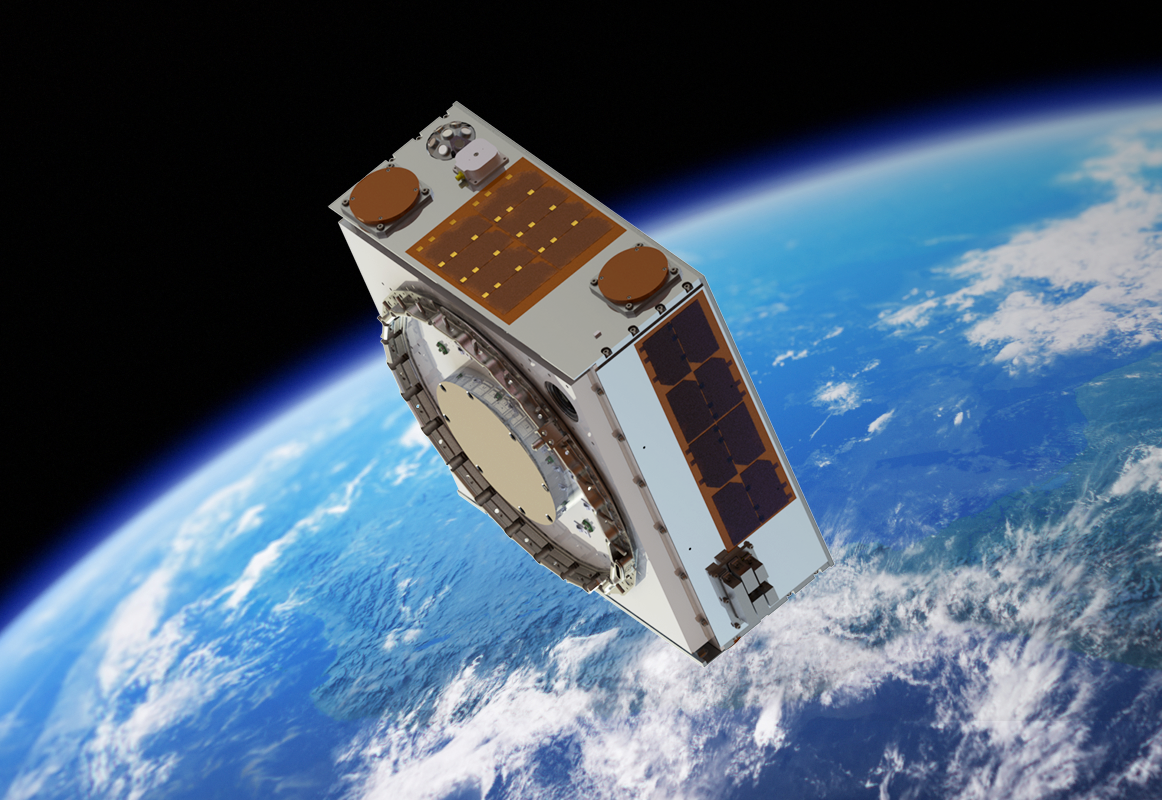

The second path is to reduce the debris that’s already in orbit. We want to go up, grab dead or failed satellites and bring them down. With our initial goal of no more debris (we call that end-of-life services), we want to prepare satellites before they launch with a docking plate. Think of the hitch of a car that can be used to collect a car if it stalls on the highway: our plate will act in a similar way. Not all satellites have this, so we want all future satellites to have this hitch. Our plate is designed with a ferrous material that can therefore be attached with a magnet. If a satellite fails in orbit and cannot be brought down to burn up in the atmosphere, we will go retrieve it with our satellite that has a magnet on it. The technology demonstration mission that we have launching in early 2020 will test this technology.

Spaceoneers: People might be wondering if space is so big, surely some debris is not a problem?

Christopher Blackerby: This is a common attitude that people have about space debris: space is huge, so the likelihood of an accident must be low. However, space is becoming democratised. This means that many more launch vehicle companies will be launching satellites (which are also getting cheaper to build). The debris problem will only increase in the coming years, so we need to be more responsible and environmentally-conscious citizens. We need to be considerate of this problem.

This attitude was once the opinion about rivers and oceans (the ocean is too big, litter and pollution surely can’t cause a problem), but now we wouldn’t even consider polluting waste in the water. We want to get to this level of consciousness with space because we believe this is an environmental issue. Not only is it the right thing to do, but it is also a business continuity issue. Companies that will be launching thousands of satellites into similar orbital planes will be at risk of increasing debris. If one dies, it becomes a threat to their other satellites, as well as other companies. Accidents would reduce service to their customers, and thus result in significant profit losses. To assure businesses remain stable, we need to make sure that debris is removed. Consider a car that is broken-down in the middle of the highway, it is a risk to other drivers and slows or interrupts various transport operations.

Spaceoneers: What about the legal issues of space debris? Who is addressing this and are you involved with these considerations?

Christopher Blackerby: We like to think of a Venn diagram for the three issues at play here. One is technology, another is the business case (who is going to pay for this), and the other is space policy. All three are related and impact the other. On the space policy side, there is no one government or regime that has legislative control over the orbital environment. There are no documented rules or regulations that everyone must abide by, we do not have that luxury. We need to start forming norms and standards from governments, regulators, operators, intergovernmental organisations and more. All of these groups need to be working together to decide how best to move forward. Of course, this is not easy, as trying to get all these actors to collaboratively decide on an issue that is not fully regulatable is a challenge. But, we are involved in a variety of different areas on this, including discussions with domestic governments to inform them of the problem and working with intergovernmental organisations (such as the UN and World Economic Forum) about how best to apply these considerations. We are also talking with trade organisations, as people recognise that space is going to be more crowded, so satellite operators are getting together in advance of more regulation being applied, and discussing how all actors should ideally behave and act. There are many different actors, ideas, and issues coming together. Hopefully we can create a set of common norms and standards, and we are currently actively involved in these important discussions.

Spaceoneers: Tell us some more about this technology demonstration. What sized objects are you hoping to ideally collect?

Christopher Blackerby: Our technology demonstration mission in 2020 will launch a chaser (160kg) attached to a small target (15-20kg). When it gets to orbit, it will separate and connect several different times with several different permutations (such as varying stability). We want to prove our capability for potential customers, particularly those planning large satellite constellations and including satellites ranging from 150kg to 500kg.

We think there will be a recurring need for this service in the same way that a tow truck is a recurring need when cars break down. It is expected that 5-10,000 satellites will be launched in the next 10 years, which is more than the total amount launched in the past 60 years. Thus, there will be a stronger need to bring things down from orbit. We see this as a recurring mission. Imagine if 5% of satellites launched in a year are not working and are therefore considered debris, this is hundreds of potential satellites and missions.

The aims of active debris removal (to grab what is already there) is challenging. We don’t have that metallic plate on existing satellites in orbit that we can connect our chaser too. This means that we need to grab the satellite some other way (like with a harpoon or net). We are working on this capability as well and are envisioning what this could look like. If we target one or two retrievals of large satellites or rocket parts per year, we can still reduce the possible risk to operational systems in orbit. By doing this steadily, we can reduce the chance of an accident or disaster.

Spaceoneers: How does your company and other organisations track these possible debris paths and congestion growth?

Christopher Blackerby: Many different organisations and agencies are working through models of how things might look in the coming years. If we are correct and there are in fact up to 10,000 satellites launched in the next 10 years, we then consider success rates. For example, if only 90% successfully de-orbit at the end of life, the debris population over this period, will increase by several hundred to a thousand. All of this modelling is being done around the world and we are doing much of this from the ground. Many models are also responsible for tracking the debris that is currently in orbit. For the pieces that are around 10cm in size and larger, we have a strong knowledge of their activity.

At the time of the interview Astroscale had raised a total of $53 million in venture funding. Subsequently, on October 31, 2018, Astroscale announced an additional $50 million of funding, bringing the total amount raised to $102 million. See their press release here.